Creating a poster

Poster design: from sketch to poster, Cappiello’s creative process

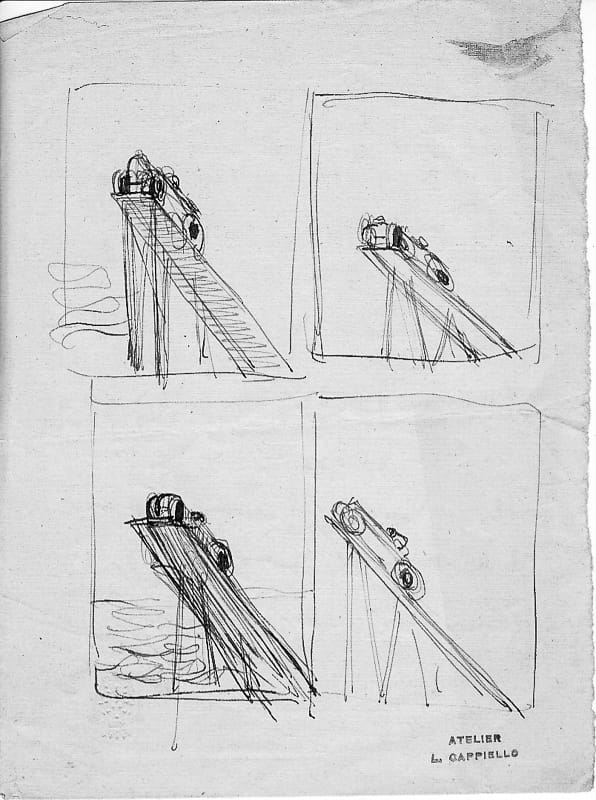

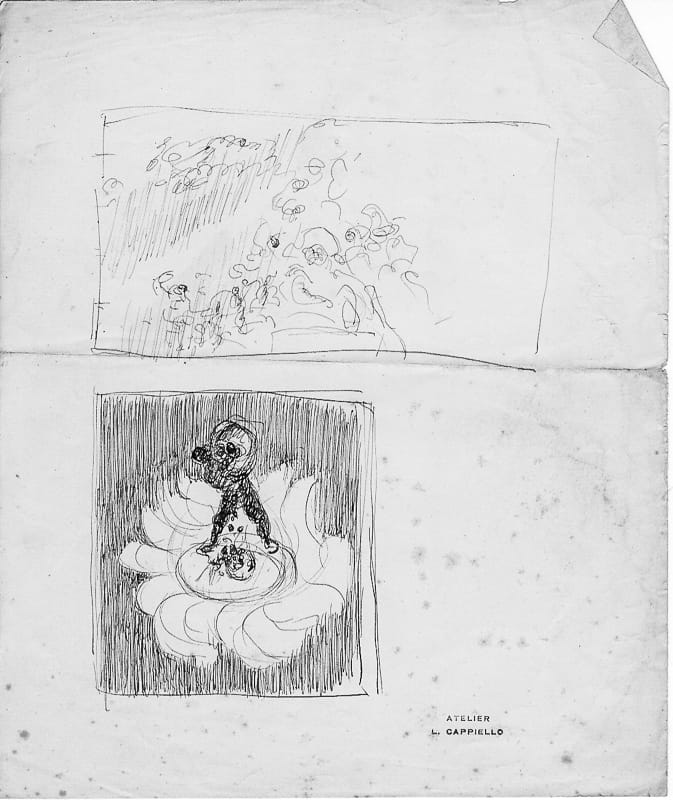

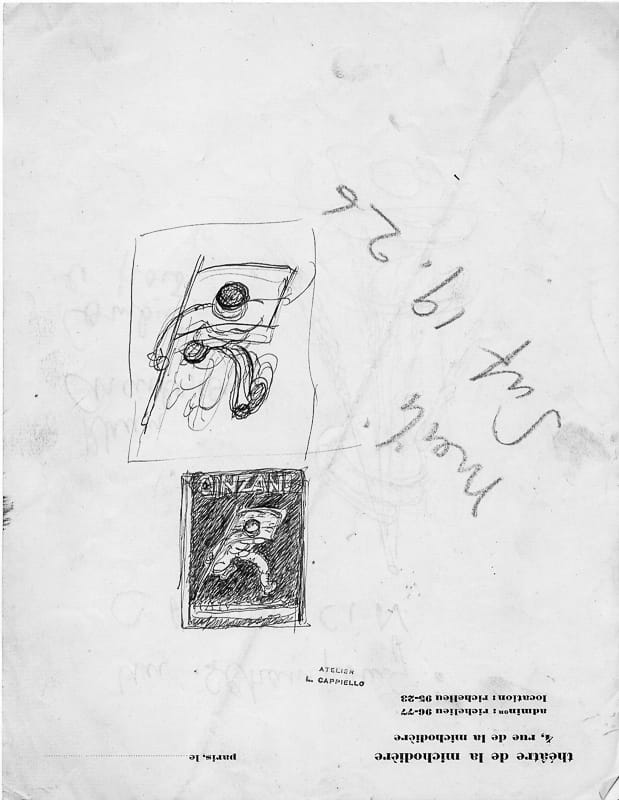

Thumbnails

A customer asks for a poster for a specific product. How does Cappiello go about designing it? Knowing that his imagination knows no bounds, and that he has a thousand ideas an hour, the process of creating a poster begins by putting down on paper the first ideas that come to mind. To do this, he uses any “piece of paper”, often the size of a postage stamp: the corner of an envelope, the back of a shopping list, a wedding announcement, etc… The surface of the paper is used in all directions. Then he works on the idea until the final arabesque catches the eye of the passer-by.

These graphics are done in pen or pencil.

But Cappiello thinks in color. Indications of this are frequent.

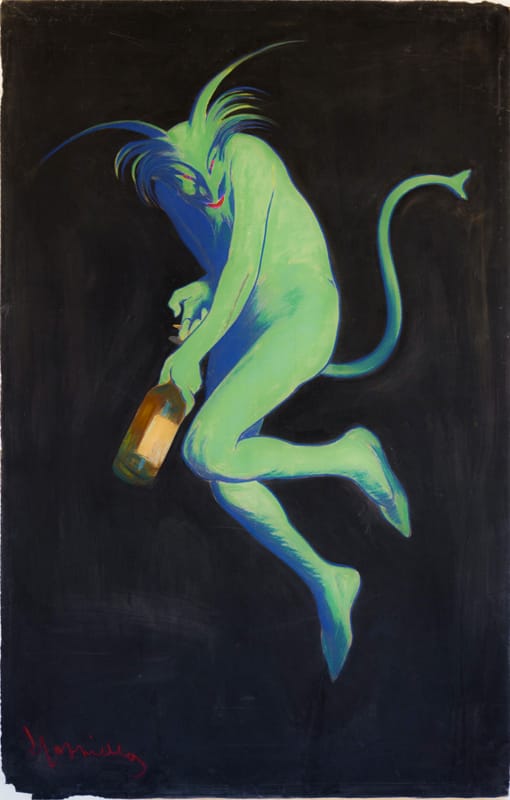

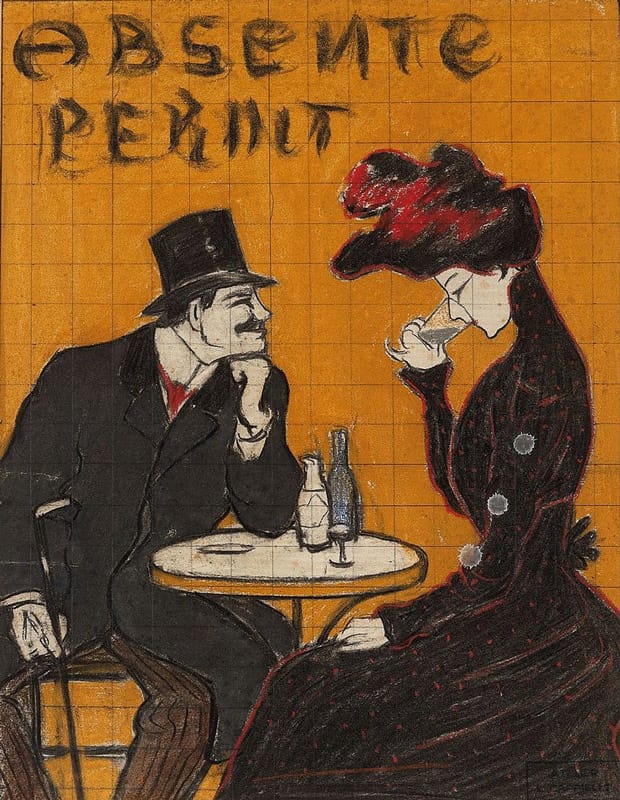

Absinthe J. Edouard Pernot (1901)

The sketches

Sketching is a crucial step in the poster design process. You can’t ask a client for anything until you’ve shown them what you’re going to propose. Cappiello begins sketching on a sheet of paper. As his imagination develops, he needs more and more space. He has to glue additional strips of paper at the top, bottom, right or left. It’s not unusual to see additions on all 4 sides.

The final dimensions of the sketches range from 50 x 40 cm for the smallest to 100 x 80 cm for the largest.

He doesn’t go back on the arabesque he’s chosen. In general, if there are two copies, the second is more accomplished and includes letters. But to satisfy a customer’s requirements, he may present several different projects. Projects not sold will be offered to others after adaptation.

With Vercasson, sketches are presented to customers in the state in which Cappiello made them, with just a simple stamp from the P. Vercasson printing house on the back. Vercasson stamp on the back.

With Devambez, the technique improved. To make the sketch more attractive, the publisher stiffens it by gluing it to strong paper or cardboard. A passe-partout and a protective flap are added. On top of the flap, a Devambez label indicates the title of the work, followed by an inventory number ranging from 5000 to 6101. To allow vertical presentation to the customer, a hanging string passes through an eyelet in the upper part of the passe-partout.

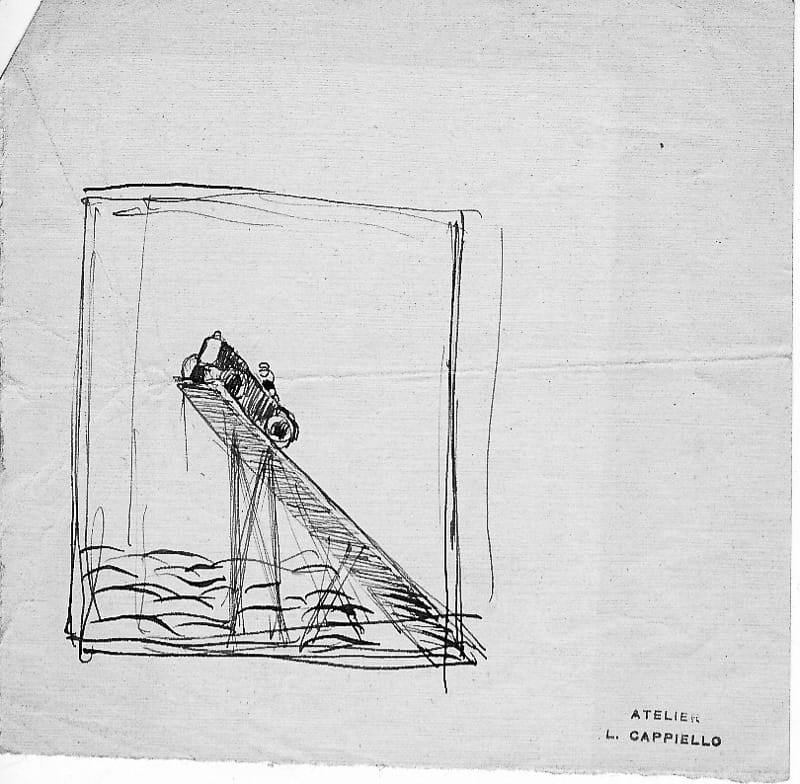

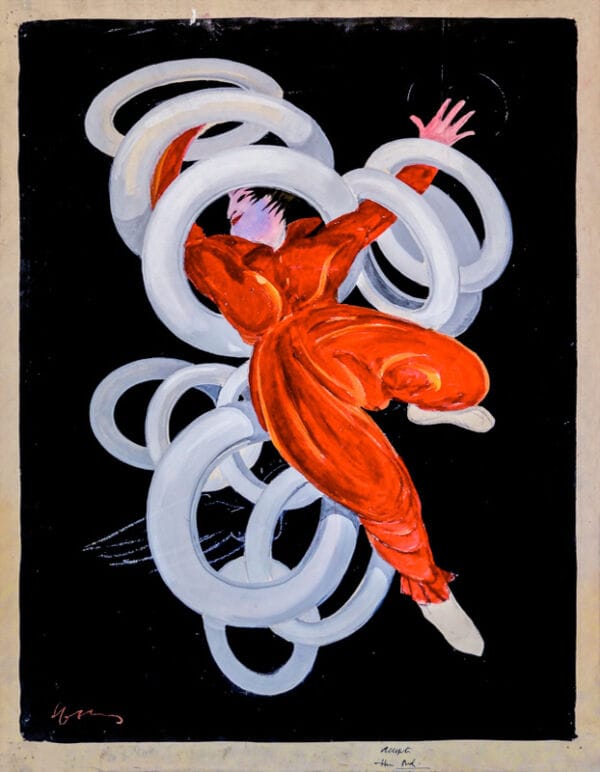

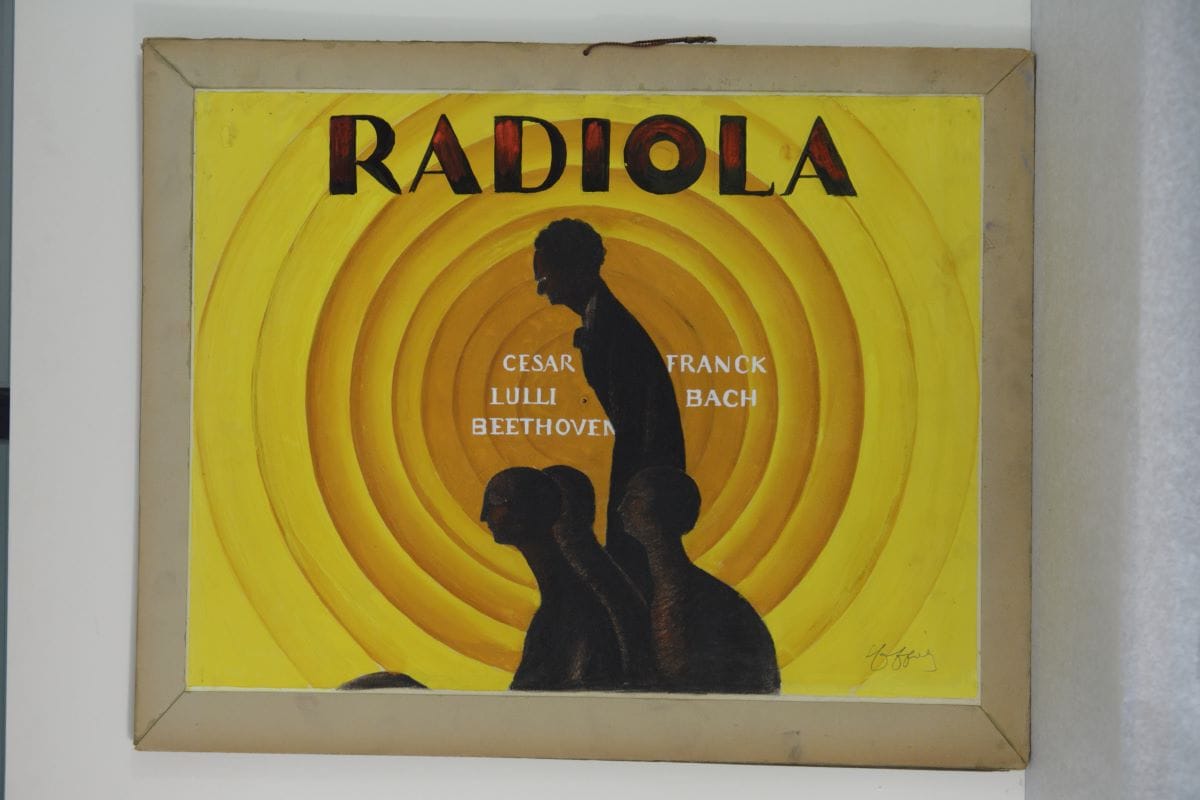

Radiola (1929)

Black and white photos

From 1912 onwards, following a lawsuit they had won for counterfeiting a hair lotion, Vercasson and Cappiello decided to photograph all new sketches in black and white and register the images with the French Institute of Intellectual Property (INPI). Additional prints were pasted into albums to serve as inventory or to present to customers.

During the Devambez period, the method became more systematic. The photos were taken in 18 x 24 cm format. Only one photo is pasted per page of the inventory album. The name of the work, its date of creation and the inventory number are indicated on each page. A section is reserved for loan management.

The Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris holds a copy of some of these albums. These photo books form the basis of our catalog raisonné. Reading them, we realize that we’ve lost track of many sketches.

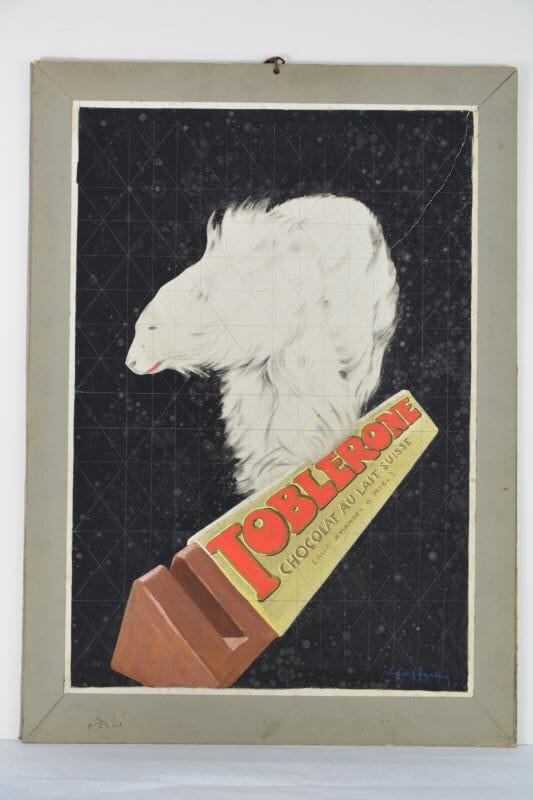

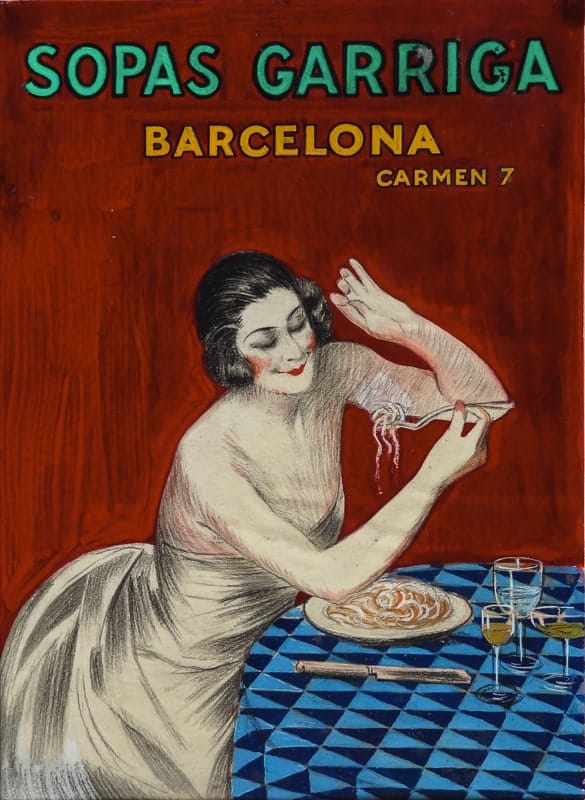

Painted photos

The size of the sketches made them difficult to present to the customer. This is why Cappiello, Vercasson and above all Devambez resort to painted photos.

The photos for the albums are printed in several copies. At least one is painted.

At Devambez, the photo is glued to cardboard and painted like the original, framed with a passe-partout or better centered. A flap is added for protection. The back usually bears the “Devambez” stamp and the inventory number.

The finished set still measures approximately 25 cm x 32 cm overall.

In the Vercasson period, painted photos are generally signed. This is rarer in the Devambez period. They were sometimes used as print orders.

Note: the painted photos of a sketch are taken a few days apart, using the same gouaches (except when Cappiello wanted to test a different color, a rare occurrence). If in this Catalogue raisonné the colors are sometimes different, this is due to the fact that the photos were taken under different conditions (photographer, camera, light).

The advantage of these photos is that Cappiello can easily make variations by painting them differently, e.g. cropping, changing color, adding or removing a detail, adding letters (e.g. “Pâtes Alimentaires” or “Sanitas”). They are easy to transport and well protected. Although painted photos are not really part of the process of creating a poster, they are very important in helping the customer to refine his or her choices.

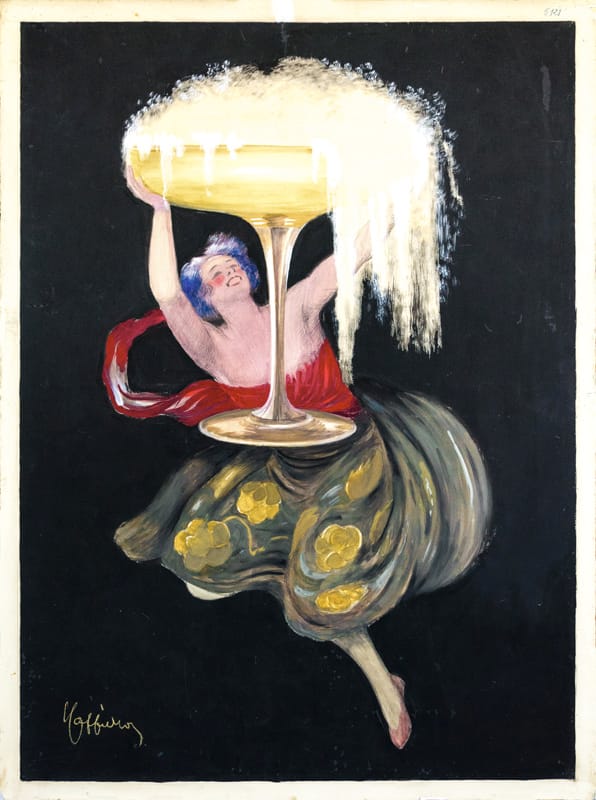

Maquettes

Once the sketch has been approved by the customer, Cappiello begins enlarging it to 200 x 130 cm. He works on canvas paper mounted on a stretcher. The models are painted with gouache or pastel. Their backgrounds are often large, highly-worked tempera solids, giving them a texture that enhances the arabesque and prevents monotony. In the drawings, numerous details bring the subject to life. In “Contratto”, for example, the white touches of the dress, positioned without any symmetry, give it lightness, while the pastel moss is particularly evanescent. This is where Cappiello’s talent shines through, making these models true masterpieces.

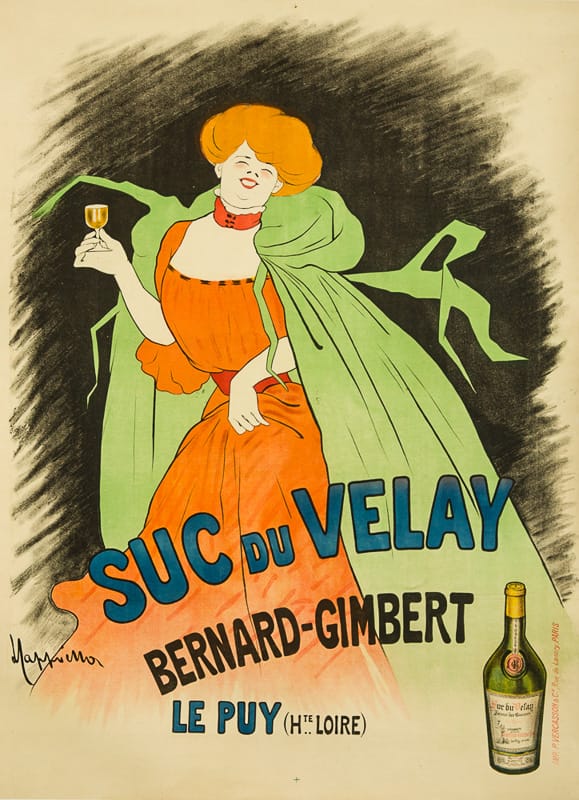

Unfortunately, a maquette isn’t always enough to win over a customer. A second one is necessary. Sometimes the maquette isn’t even sold. It is then offered to other customers. This was the case with the model made for “Champagne”, which was finally sold with a small adaptation to “Suc du Velay”.

The lithographs

The poster is printed using the lithographic process. Each sheet is pressed onto an intaglio stone, filled with ink of a single color, as many times as there are different colors.

Cappiello assists with the printing. If necessary, he makes minor adjustments to the stone and checks the colors. Under these conditions, the poster is said to be “original”. For reprints, Cappiello’s presence is not systematic.

Some posters were printed for the first time without Cappiello’s presence. One example is Parfums Blamys. The poster, owned by Vercasson, was sold after the end of the contract with Cappiello. The same is true of Barbier Dauphin, published after his death. In these cases, the signature is completed by the words “D’après” (“After”).

The measurements given in this catalog for lithographs are the dimensions of the sheet of paper, without taking into account any canvas backing.two similar prints may differ by several centimeters, as it is common practice to cut off part of the damaged margins during restoration. Differences in humidity and temperature can also have an influence.